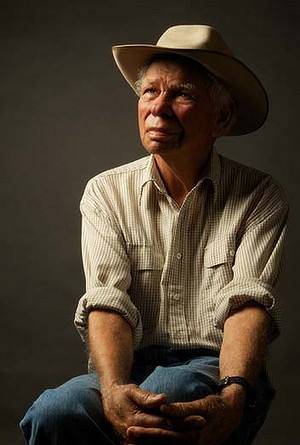

Reconciliation Week with Uncle Herb Wharton

In the spirit of reconciliation and to help our Team and Board at SQ Landscapes better understand and work with our region’s First Peoples, we took part in a special online event during Reconciliation Week (27th May - 3rd June) to hear from two amazing Queenslanders. Elders Aunty Ruth Hegarty

and Uncle Herb Wharton kindly gave some of their time to recount their respective stories about what it was like for them growing up Aboriginal in Australia and their views on the path to reconciliation.

Since our company's experience hearing Uncle Herb's stories during Reconciliation Week, he has been awarded Member (AM)

in the General Division for 'significant service to the literary arts, to poetry, and to the Indigenous community' as part of the Queens Birthday Honours.

We congratulate Uncle Herb on this significant and well-deserved accolade.

Image credit: By Ali Sanderson via Huffington Post.

Uncle Herb Wharton of the Kooma People

Uncle Herb Wharton was born in Yumba, an Aboriginal camp in south west Queensland near Cunnamulla.

“I was born in 1935 or 1937 – I forget because they didn’t keep records of aboriginal people back then and I didn’t get a birth certificate.” His biography confirms he was born in 1936.

“Then, Cunnamulla was a town where Aboriginal people weren’t allowed to live in town. Growing up down there, even though I got chased with a stick going to school, it was good, we learned dreamtime.”

“I’m glad they forced me to go because I came to realise how important it was to read and write. There was still a lot of racism.”

Uncle Herb recalls that the top camp in Cunamulla had no taps, and the bottom camp they had to walk to the tap at the cemetery.

“My dad would say to the teachers, ‘you can give him the cane or whatever but no homework, because when he gets home he needs to go and get water’.”

“I learnt from the earliest age where my tribal land was, that’s what’s lacking in young people today.”

He says he was more fortunate than some, that he never lost his identity or connection with the land.

“So many of my people were sent to missions to learn white history and religion,” he said.

“I remember when I was 7 or 8, there was a big truck coming in from Thargo (Thargomindah) with lots of kids about 5 or 6 years old, and they were going to put them on a train and send them to Cherbourg.”

“I was talking to some of those kids, and then I got told to bugger off or I’d be in there with them. I wasn’t old enough to realise the significance of the kids being taken from country.”

“My mum told me that where she grew up, when anyone ever came they had to run and hide out the back. But they were protected by a bloke who would stand at the door with a gun.”

When he finished school, Uncle Herb began droving all over outback Queensland and New South Wales. He recalls reading all about Burke and Wills discovering parts of the land but knew that they were seeing for the first time what formed the culture of First People for many generations before.

“It’s not so much about owning the land but belonging to it,” he says.

Uncle Herb saw a lot of the countryside on horseback while droving.

“Eventually I gave up drinking and smoking and had nothing else to do, so I started writing.”

“I’d read a bit of Banjo Patterson and Henry Lawson and they didn’t know too much, so figured I could do a better job.”

Uncle Herb wrote his first book of poems called ‘Kings with Empty Pockets’ in the 1980s and after entering them in the David Unaipon Awards for unpublished Indigenous writers and being highly commended, the University of Queensland Press commissioned him to write a Novel. His novel was published in 1992 and is called ‘Unbranded’, detailing his experience on stock routes in outback Australia.

This was followed by ‘Cattle Camp’ in 1994, ‘Where ya' been, mate?’ in 1996, and ‘Yumba Days’ in 1999. Herb recently finished a first draft of a novel called ‘The Munta and the Mob’.

On reconciliation, Uncle Herb believes that handing back Native Land Titles would go a long way towards achieving reconciliation.

“Land rights are important part of reconciliation – we’ve never sold any of it away.”

“I would like to see Native Title given back by the government. I have eight brothers and two sisters, we knew where our country was but now I’m the only one left.”

“I’ve written about some things, but there are other things, I’m unsure how to pass them on. I sometimes wonder who the right person is or do I let it die with me?”

“When my uncle Joe died he left me some things. He told me if they fell into the wrong hands it could cause some strife. So do I pass that on, who I tell about some of these things? I have records and scribble that I have to find ways to safeguard for the future.”

As Uncle Herb expressed his concerns about passing down his stories and history, he recalled a trip he made to Sydney, and a story he was told there.

“I got to go to the Opera House and a fella there reckons that as the people on the land watched Cooky sail into Sydney Harbour, he reached for a wooden thing that the fellas on shore thought was a didgeridoo. But instead of putting it up to his mouth, he put it up to his eye. The First People thought what a silly bugger, playing a didgeridoo with his eye and fell about on the ground in fits of laughter, which is how Cook got the idea no people lived here in the first place.”

“You have to laugh at the history,” he says through a smile, “otherwise you’d cry.”

Uncle Herb still lives in south west Queensland where he was born and says relationships these days around Cunnamulla aren’t any worse than they were back then.

“There’s still discrimination, but I’m proud of who I am.”

“We’ve gotta get rid of the perception of race – there’s no such thing as a different race – we are the human race.” Find Uncle Herb’s books on Booktopia.

Image credit: Goondiwindi Argus

Southern Queensland Landscapes is seeking an experienced and influential Board Chair to lead a multi-skilled Board in managing natural resources across Southern Queensland. This is a 3-year remunerated role based in Toowoomba, QLD, with the flexibility to manage from anywhere in Southern QLD. The ideal candidate will bring: • Substantial experience leading diverse Boards • Strong relationship-building and leadership skills • Expertise in environmental and agricultural matters This role is an opportunity to shape the future of natural resource management, working closely with land managers, community leaders, and industry professionals. Are you ready to make an enduring impact? For more details and to apply, visit www.windsor-group.com.au/job/board-chair-natural-resources-peak-body or contact Mike Conroy at apply@windsor-group.com.au.

This week marked the final Board meeting for retiring Southern Queensland Landscape Chair, The Hon Bruce Scott AM. The Southern Queensland Landscapes Board hosted a function at Gip’s restaurant in Toowoomba, joined by past Directors, industry stakeholders and the Southern Queensland Landscapes Management team, where Bruce was warmly acknowledged and thanked. Bruce offered special thanks to his dear wife Joan for her support during his period of service to Southern Queensland Landscapes, in particular the warm country hospitality she has offered to many visitors to Roma. Bruce also recognised and thanked Southern Queensland Landscapes Company Secretary Pam Murphy, who has supported Bruce in his service to Southern Queensland Landscapes since the organisation’s inception.

The Condamine Headwaters, a critical ecosystem in Southern Queensland, has long faced threats from sedimentation, habitat degradation, and thermal regime changes. The Blackfish Project, dedicated to reversing these impacts, unites scientists, landowners, and the community in a shared mission to restore and protect this vital environment. At its core lies the river blackfish, a sensitive indicator of the overall ecosystem health. Central to the project's success is the unwavering commitment of landowners like Paul Graham. Inspired by the project's vision, Paul reached out to SQ Landscapes seeking support for a solar pump and tank to divert his cattle away from waterways on his property. Paul's deep-rooted love for his land, captured in his humorous quip "I love my land more than I love my wife," is a testament to the powerful connection between people and place that drives conservation efforts.

The Board of Southern Queensland Landscapes recently met in Toowoomba. In addition to the Board meeting, Board and Executive worked through updating SQ Landscapes’ strategy. Company Secretary Pam Murphy highlighted the importance of the latest Board meeting and what it means for the company’s future. “The updated strategy will help SQ Landscapes deliver sustainable natural resource management (NRM) outcomes that improve the lives of people in regional communities now and for the future,” Pam Murphy said. “We’re excited to continue delivering value for our region and build Flourishing Landscapes and Healthy Communities across Southern Queensland under the guidance of the Board,” Mrs Murphy said.