Reconciliation Week with Aunty Ruth Hegarty

The Reconciliation Week theme 'In this together' is now resonating in ways we could not have foreseen when it was announced last year, but it reminds us whether in a crisis or in reconciliation we are all #InThisTogether.

In the spirit of reconciliation and to help our Team and Board at SQ Landscapes better understand and work with our region’s First Peoples, this week we took part in a special online event to hear from two amazing Queenslanders. Elders Aunty Ruth Hegarty and Uncle Herb Wharton kindly gave some of their time to recount their respective stories about what it was like for them growing up Aboriginal in Australia and their views on the path to reconciliation.

Aunty Ruth Hegarty of the Gunggari People

Aunty Ruth is almost 91 years old. “There aren’t too many people older than me,” she says.

Ruth and her mother Ruby travelled from their home in Mitchell when she was just 6 months old to Cherbourg which the family thought would be just for a little while. Confined by the rules of the ‘Protection Act’ Ruby and Ruth were forced to stay in Cherbourg and were placed in the dormitory system.

Aunty Ruth lived in a dormitory in Cherbourg with around 60 other girls where they were treated like prisoners despite committing no crimes. Mothers would live on one side of the dorm and children on the other side.

The children were whipped, punished physically and psychologically for minor misdemeanours and when she was just 4 years old, Ruth’s mother was sent away to work, causing the pair to lose contact.

Most of us can’t fathom growing up like this or having our mothers taken away from us at four years old, but this was just the beginning of her journey.

10 years later at 14 years old, Ruth herself was sent away from the Cherbourg Mission to work as a domestic servant. She felt alone, isolated and vulnerable travelling to work for strangers.

She experienced no freedom for 22 years before persuading her husband to leave Cherbourg for Brisbane so that their children could live a better life, which they eventually did only because he had an exemption as part of the 1967 referendum. Without this exemption, she was not allowed to leave Cherbourg.

“I spent 20 or so years of my life in Cherbourg, before realising that wasn’t the place for me. Living life in Cherbourg almost taught me not to speak out to those in power.”

“I’ve never known myself to be an Aborigine, because no one ever said 'you’re Aboriginal' – but I found out what it was like when I got married.”

Ruth fell in love, but her husband treated her the same way she had been treated as a dormitory girl.

“The first thing he said to me was ‘I own you’, but I didn’t want to be owned. For the next 15 years he had complete control over my life.”

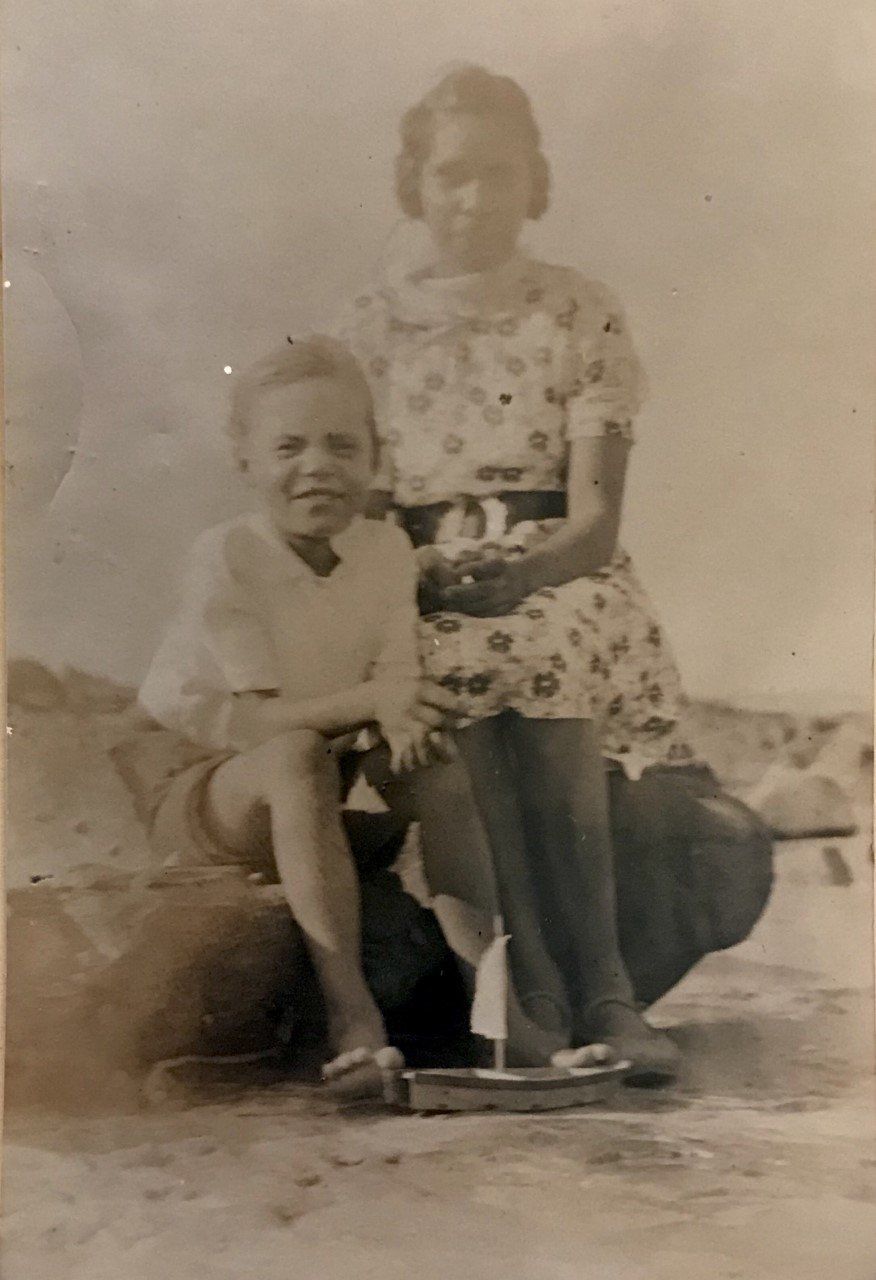

Photo: Supplied. Aunty Ruth with her mother Ruby.

Ruth has eight children, one adopted, 36 grandchildren, 72 great grandchildren and 29 great great grandchildren.

She didn’t know about her father until she was 56 years old and met all of her half brothers and sisters in Mitchell when she went back. She wasn’t able to learn the Gunggarri language of her people growing up, and is still learning about it now at 90 years old. “It’s a beautiful language,” she says.

Ruth remained connected with the dormitory girls she had grown up with. “We would only talk about life in the dorm to one another, never our children or other people. Those women are my sisters – my family.”

“Before my husband died, he told me to write about my experiences, and by doing this over the past 30 years, I have found myself.”

In Aunty Ruth’s two published books ‘Is that you Ruthie?’ and ‘Bittersweet Journey’, she recounts her personal history as one of the Stolen Generation, her married life, her dealings with the Native Affairs Department and her work in community politics and indigenous organisations. Nowadays, she continues to recount her experiences by public speaking, as an author and writing articles for Facebook.

About reconciliation Aunty Ruth says, “It has to come through acknowledgement, that’s how reconciliation will happen.”

“Acknowledging our language like naming streets after Aboriginal people, let’s do more of that, instead of naming things after Captain Cook.”

“It is important to understand the history of this country, this country belongs to Aboriginal people and we are very willing to share. We need to teach our children the stories too – I’ve got grandchildren of all colours; blue eyes, green eyes, brown eyes, red hair, brown skin - they need to know their story, it’s a shared history.”

“Reconciliation is something I love. I love to think we are reconciled with one another. I have never been an enemy with the white man. Reconciliation is people coming together, we must close this gap. Reconciliation will only come when the gap is closed. We live in a better Australia now. We have no enemies except the one we make for ourselves.”

Photo: Supplied. Aunty Ruth today.

Southern Queensland Landscapes is seeking an experienced and influential Board Chair to lead a multi-skilled Board in managing natural resources across Southern Queensland. This is a 3-year remunerated role based in Toowoomba, QLD, with the flexibility to manage from anywhere in Southern QLD. The ideal candidate will bring: • Substantial experience leading diverse Boards • Strong relationship-building and leadership skills • Expertise in environmental and agricultural matters This role is an opportunity to shape the future of natural resource management, working closely with land managers, community leaders, and industry professionals. Are you ready to make an enduring impact? For more details and to apply, visit www.windsor-group.com.au/job/board-chair-natural-resources-peak-body or contact Mike Conroy at apply@windsor-group.com.au.

This week marked the final Board meeting for retiring Southern Queensland Landscape Chair, The Hon Bruce Scott AM. The Southern Queensland Landscapes Board hosted a function at Gip’s restaurant in Toowoomba, joined by past Directors, industry stakeholders and the Southern Queensland Landscapes Management team, where Bruce was warmly acknowledged and thanked. Bruce offered special thanks to his dear wife Joan for her support during his period of service to Southern Queensland Landscapes, in particular the warm country hospitality she has offered to many visitors to Roma. Bruce also recognised and thanked Southern Queensland Landscapes Company Secretary Pam Murphy, who has supported Bruce in his service to Southern Queensland Landscapes since the organisation’s inception.

The Condamine Headwaters, a critical ecosystem in Southern Queensland, has long faced threats from sedimentation, habitat degradation, and thermal regime changes. The Blackfish Project, dedicated to reversing these impacts, unites scientists, landowners, and the community in a shared mission to restore and protect this vital environment. At its core lies the river blackfish, a sensitive indicator of the overall ecosystem health. Central to the project's success is the unwavering commitment of landowners like Paul Graham. Inspired by the project's vision, Paul reached out to SQ Landscapes seeking support for a solar pump and tank to divert his cattle away from waterways on his property. Paul's deep-rooted love for his land, captured in his humorous quip "I love my land more than I love my wife," is a testament to the powerful connection between people and place that drives conservation efforts.

The Board of Southern Queensland Landscapes recently met in Toowoomba. In addition to the Board meeting, Board and Executive worked through updating SQ Landscapes’ strategy. Company Secretary Pam Murphy highlighted the importance of the latest Board meeting and what it means for the company’s future. “The updated strategy will help SQ Landscapes deliver sustainable natural resource management (NRM) outcomes that improve the lives of people in regional communities now and for the future,” Pam Murphy said. “We’re excited to continue delivering value for our region and build Flourishing Landscapes and Healthy Communities across Southern Queensland under the guidance of the Board,” Mrs Murphy said.